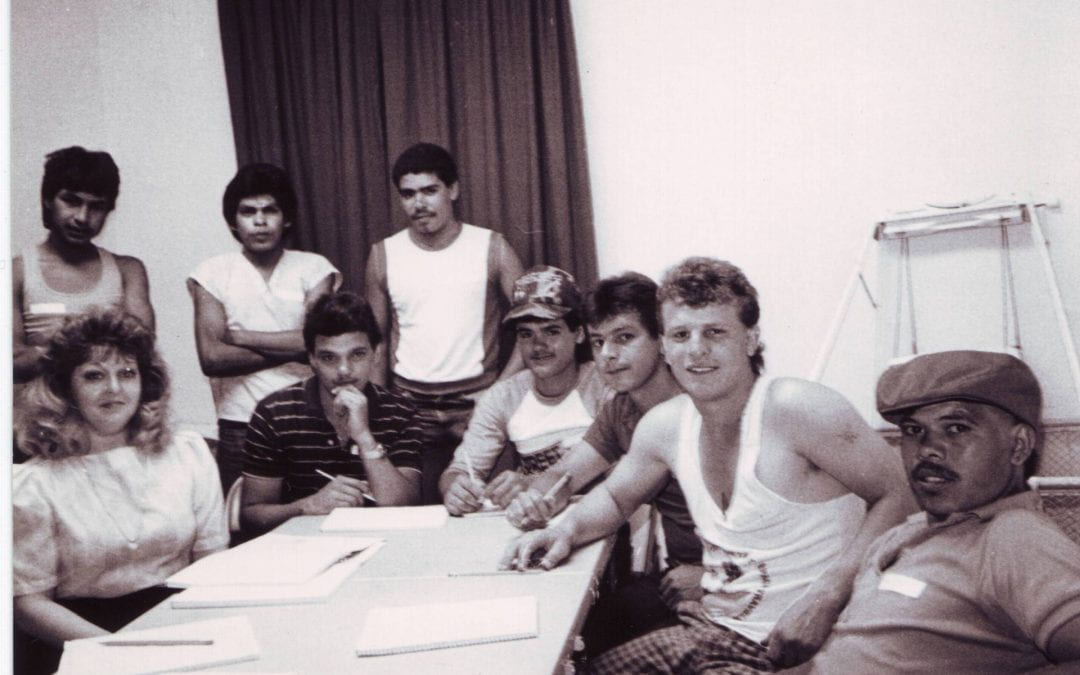

Since I put the finishing touches on Corazón de Dixie in 2015, Trumpism and its anti-immigrant rhetoric have overtaken the Republican Party. The term “pro-immigrant conservatism”—a phenomenon I documented in my chapter on rural Georgia from the 1960s-80s—today seems more than just a little unexpected. It seems downright impossible to imagine. As Duke junior Daisy Almonte writes in her recent Op-Ed about an anti-immigrant bill working its way through the North Carolina legislature, in today’s South Republican politicians race to prove their conservatism by using immigrants as symbolic pawns. But these pawns, as Almonte reminds us, are people.

And then I open the New York Times to find this: “Alabama is more pro-immigrant than you think.” The truth is that since 2011 I’ve only been back to the South to lecture, not to research. So I didn’t actually think one way or the other—I wondered.

In his op-ed, Rev. Alan Cross describes pro-immigrant conservatism, against the tide, reappearing in Alabama in 2019. He posits that his evangelical congregants have tired of the anti-immigrant rhetoric, and are returning to (in his view) more faithful interpretations of the Bible that exhort them to welcome the stranger.

I would argue that this is, in fact, the “original” response of Evangelicals to Latino immigration in the U.S. South, at least in the rural areas. Pro-immigrant conservatism always had its pitfalls, as I explore in Corazón de Dixie. The grace of white church people depended on Mexicano workers not organizing their own bases of power, thus leaving their families highly vulnerable when harsh anti-immigrant laws came to Georgia in 2011. Still, over the past hundred-plus years, Latinos in the South have pursued a wide range of strategies to secure their positions in the region. If white Evangelicals are interested in being a part of that story once again, I am glad to hear it. I hope their support will prove more consistent—and less conditional—in the future than it was last time around.